Note: This post is Part 1 of several posts about the Sedona Plein Air Festival.

Wherein the artist has his breath taken away when realizing that photos can not do justice to a place like Sedona, Arizona, only paintings can. And wherein 32 artists attempt to remedy this by creating, out of thin air, a major exhibit.

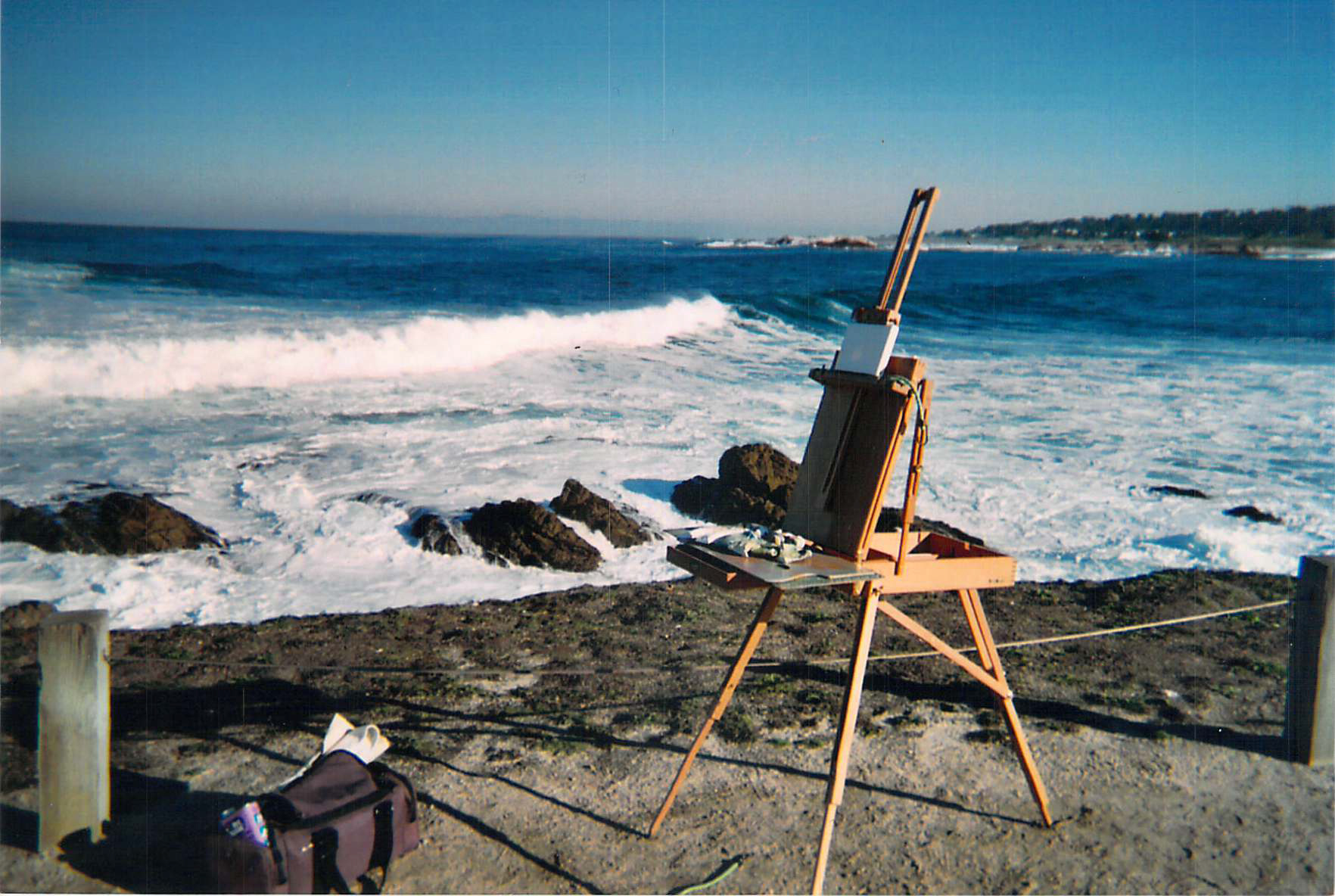

Take a moment to look at this photo. See that modest little road? Note the clearly visible bike lanes, firmly painted as if to say “bikes are as important as cars”. That’s 179, the major highway into Sedona. See the buildings, adobe-like dwellings, tucked into the grey-green trees? See the electric wires? No. And in the distance, do you see ten million years of the slow erosion of red rock? Time, aeons, evident and undeniable. And beyond, do you see the inviting skies and perfect weather?

Nevertheless, this photo in no way gives one a sense of this place. Yes, all of those things are there but, in this picture, dead and flat, is just a hint of what is real. Perhaps that is because of the 360 degree visual experience driving into this town, those peripheral images of equal beauty clicking past you, cactus, rock tree, dreamlike, making you look here, there, up, down, afraid to miss a thing, nearly driving off the road. Driving off the road. Perhaps it is because you’ve driven hours through a somewhat different desert of a different color only to come upon this place that is too vivid to be true. Our emotional response to the landscape can not be captured in a photo.

Sensory Overload

Sedona, Arizona, was new to my eyes, and I’m certain that many artists, as well as “normal” people, can relate to that wonderful sense of happy awe as you drop down into this valley. Unlike my camera, which sees nothing but light and records without comment, my brain reeled with the experience, almost overwhelmed with the color, the age, and the vivid “suchness” of the scene.

Gradually some sense of what’s ahead, in terms of work to be done, crept into my consciousness and a thought emerged. The thought, at first very primitive because I had been immersed in a right brain experience and words had failed me, came out something like “Must paint buttes. Mmmm. Buttes good.” My inner caveman was trying to come out of his cave, trying to evolve all the way up to cro-magnon as quickly as possible because another thought was urging him on: “Buttes hard to paint.” Eventually the initial shock of driving into the full-immersion, three-dimensional, sunny, sparkling valley of Sedona faded. Then the artist, the present-day plein air artist, articulated quite clearly and out loudly in perfect modern English (though with a disconcerting tinge of mania): “It’s going to be a challenge to paint those buttes!”. Followed by maniacal laughing caught up short in a sudden moment of sober thought as the immensity of it all soaked in…

Drawing Perspectives

But the adventure of the painting of the buttes will wait until the next post and those to follow, for this is a multi-post account in honor of the heroes of Sedona, the plein air artists and those who support them.

For now, let’s put the Sedona Plein Air Festival into perspective, the perspective of a million years of erosion, ancient peoples, artistic sensibilities, and modern striving. It is all an unlikely and amazing thing, this place called Sedona and this thing called Sedona Plein Air and we take it for granted, I believe. After all, it is just the world, we think, beautiful as it is, amazing as it is, but it is just the world nevertheless, in modern times. So we drive into Sedona appropriately in awe at scope of the landscape, thrilled by the color and the crystal clear air. Only after some days here do the realizations about place, especially this place, clarify themselves; realizations about land, peoples, and time, about hopes and dreams come and gone.

A Day at Sedona Beach

Pre-Cambrian Sedona, it wasn’t called that in those days, was not only volcanic but it lay at the bottom of the sea! Yet hundreds of millions of years later, just 500 million ago, the land rose up from the sea, becoming a hot desert plane on the edge of the ocean. Sedona had beaches. They stretched for miles and miles with no one in the world to walk on them because there was no one in the world. But these beaches were not to last, and the land sank and rose again over time and, around the time reptiles evolved the area again had beaches and Sedona sat perched on the western edge of that great and ancient continent geologists call Pangea. The reptiles are still here, by the way; I spotted a young shop girl gingerly carrying one out and placing it in a planter outside. Must be her daily chore. Perhaps in those ancient days the only thing walking on the beach were reptile sweethearts. In any case, we know there were no people until long after the rising and falling of the land created great sedimentary deposits and sand dunes which would solidify into red rock and erode over time to what we see now.

Early Plein Air Artists

Time passed and, as theory goes, humankind found its way from Africa to Asia to North America. One day, a band of humans came over a ridge, where years later Highway 179 would run, and they looked down into the valley and, boggled at the sight, found their brains swirling in a wash of mixed thoughts that may have sounded something like “Must paint buttes. Mmmm. Buttes good.”. We don’t know for sure if they ever painted the buttes in those days, but we do know they nestled their encampments next to the buttes and drew on them in minerals and charcoal. Centuries later these little plein air pieces can still be seen at Palatki. Would that the paintings we painted during this competition will stand such a test of time.

Clearly, the meanings captured in these simple images are relevant and understandable to us nearly nine centuries later. But I should not call them “simple” for I have to wonder if the artist offhandedly sketched a quick stick figure or if the artist has masterfully distilled hope, beauty, and life experience into a kind of ultimate abstract expression of art? But it isn’t healthy to intellectualize too much.

In any case, the pictograph was painted outdoors on an overhanging rock wall. For me, that’s as close enough to plein air as some of the work I have seen. What was the artist’s name, we wonder. Or, is that the artist’s name? The artist stood in that place for some time, fully a part of the surrounding, experiencing it bodily. Could it be that this little stick deer is the signature to a life lived out in the open air?

Modern Times

Our sensibilities are different from those early tourists who came over that ridge where 179 is today for, unless we get our feet off the gas pedal and onto the red rock ground, we can never fully feel the world around us anywhere, let alone understand Sedona’s landscape. But that is generally speaking only, because for a plein air artist it is so very different. If you are a plein air artist you can skip this part; if not, let me describe something that our early plein air pictograph artist knew: you have to stand in the environment, right down in it and on it with both your feet and you must do that for a long time to truly “get” a place. It takes time for the stillness of your presence to encourage the land and its lizards, birds and insects, to become comfortable with you being there. But when they are comfortable, you have reached that fine point where apprehending the essence of the landscape around you is like reaching for a fruit that is ready to be picked. Reach out and pluck it. Put it on canvas.

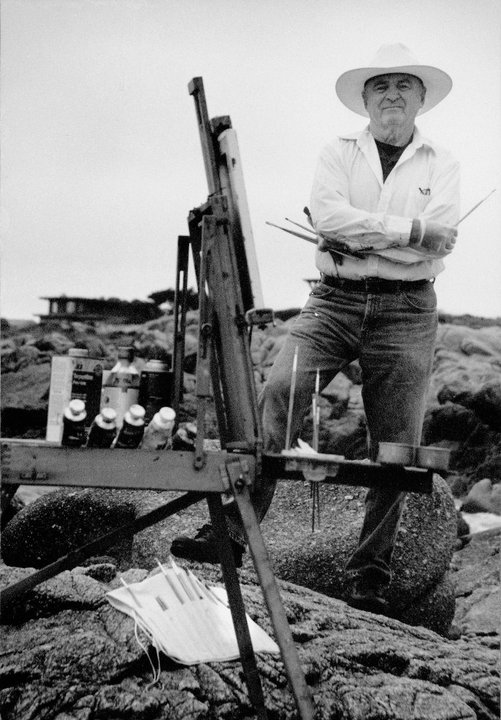

In the rush to get somewhere fast, few of us even slow down enough to ride a bike (see “My ‘Ride'”), let alone hike a trail, let alone stand still in a place for three hours. But plein air painters do that. It isn’t always easy, and it is definitely work. But, as artist Scott W. Prior posted recently, “This is my office.” As artists, we bring our 21st century artistic and cultural sensibilities to a place in the environment and we stand still and work hard to create something out of nothing with a sort of hell-bent bravura that any American would be proud of. Where there were no paintings now there are many, and we hope that our pictographs speak to others and to generations to come with the same dignified eloquence as those painted on rock a thousand years ago.

Coming Up

This is Part 1 of a series of posts on the Sedona Plein Air Festival. More coming in a day or two. I’ll be covering challenges, locations, quirky and freaky incidents, styles, intellectualizing things to death, and technical challenges. Tim Poly and others have graciously allowed the use of many fine photos so don’t miss the next posts.

– End of Part 1 –